Hello! We're building a spatialized metaverse from a volcanic island

Caitlyn Meeks here, CEO & co-founder of Tivoli Cloud VR. With Maki Deprez, CTO and co-founder, we've been keeping super busy from our lair atop a remote volcanic island. Not kidding– we've been working hard from the idyllic volcanic island of Tenerife, off the coast of west Africa.

Unlike a super villain's volcanic island lair from a James Bond film, ours doesn't include an atomic doomsday laser, but does have shirtless German tourists and open air restaurants. It is from here, the volcanic island of Tenerife, that we started engineering a spatialized metaverse architecture.

By we, I mean Caitlyn Meeks, former chief evangelist at High Fidelity (that's me), and my partner, our CTO and co-founder, Maki Deprez, an accomplished programmer and VR content creator. Together, we're building a spatialized metaverse on the architectural foundations first laid by the open-source virtual reality company, High Fidelity. We believe this architecture, and its future progeny, will become the foundation of the spatial networking metaverse we've all been waiting for.

In this and future blog posts, we'll explain why we believe this is the way to go. We'll talk about the features and functionality we're adding and changing in our distribution. And we'll discuss our philosophical differences on important matters like user experience, product design, community support, and commerce.

Game engines weren't made for this.

I remember the day we got an Oculus DK1. I worked at Unity then, and experiments with the headset and Hydra hand controllers promised a glimpse of a coming first wave of consumer VR. Later on, ExitGames' Photon Cloud multiuser networking SDK appeared in our Asset Store submission queue. It was clear how easily someone could snap these together to make a multiuser VR chat app. It wasn't long before they started to surface, notables including AltSpace, Rec Room and VRChat. With a Unity based client and Photon running the back-end, there wasn't a lot of heavy engineering to do, giving indie developers an opportunity to experiment and have fun. The fun and novelty of social VR attracted users, drove entirely new kinds of live events, and fostered vibrant meme-based subcultures in spite of numerous technical constraints. Alas, once the platforms grew in concurrent users, however, these constraints became a real problem and the novelty began to wear off.

When you want a reasonable group of people in the same room at the same time, the joists under the floor start to creak. The experience degrades. The network bogs down. Lag sets in. Your frame rate drops. Streamed audio is crudely attenuated. People talk on top of each other. User generated content crashes the client. Features made to help game developers turn into exploits for malicious users.

Game engines weren't designed to create an elegant spatialized metaverse.

Not-ready Player One

I spotted Ready Player One at a bookstore in 2012. I was impressed by level of detail depicted in Kline's fictional The Oasis metaverse, and considered the architecture of such a system. It'd need to handle petabytes of network packets routed and rerouted between hundreds of thousands of servers, millions of clients. And it would need client software designed to shape it into a nuanced dance of human interaction.

This requires a new kind of thinking. This is a computer science problem, not a game development problem.

Building a true spatial metaverse architecture

When I caught word that Philip Rosedale's new company, High Fidelity, was working on cracking the metaverse architecture problem, I left an edifying career of seven years at Unity and joined the company. First thing that struck me when visiting the office was spotting "You can't just copy code from Stack Overflow" penned on the stairwell wall. The High Fidelity team was an extremely sharp group of engineers, many were former senior developers behind the popular virtual world, Second Life, and computer scientists who wrote the first media streaming codecs at Real Networks.

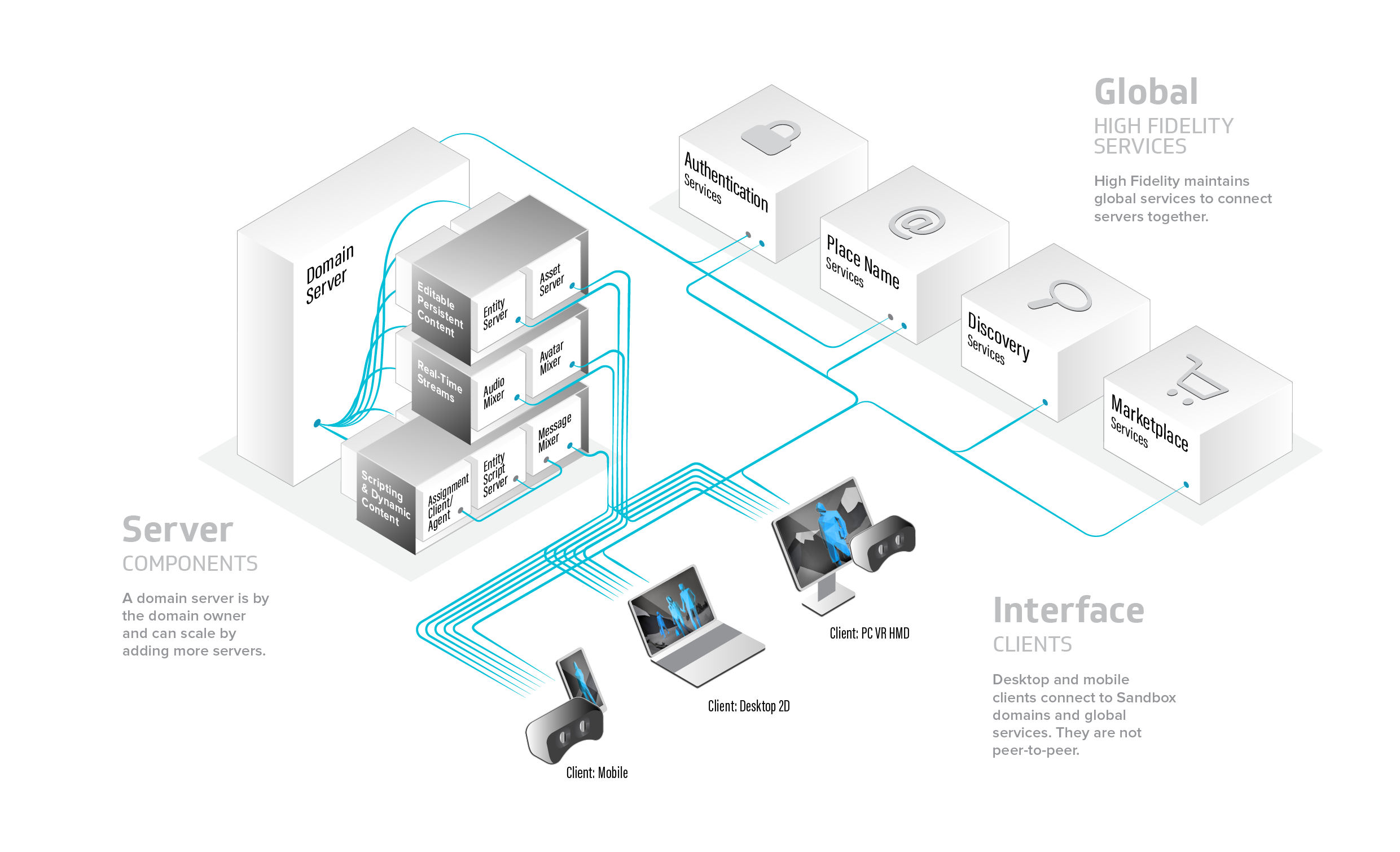

"We're throwing the full Hail Mary" to create the metaverse, one of my coworkers once put it. Engineers covered whiteboards with plans for an avatar-mediated metaverse architecture: a custom client built from scratch to stream, process and render avatar, audio and entity data as quickly and efficiently as possible. A server stack with discrete components for processing simultaneous streams of avatar skeletal information, entity operations, spatialized 3D audio streams, manage authoritative physics, script execution and inter-domain messaging. And notably, the design called for decentralized servers that could run on anybody's hardware, while communicating together via a central DNS grid server. Audio was of utmost importance, and R&D created what is arguably the best sounding, most nuanced, and lowest latency 3D spatialized voice streaming system ever made.

This research culminated in software capable of handling several hundreds of avatars in a single instance of space simultaneously, while delivering low latency, nuanced and spatially attenuated audio, conveying subtle body language from just headset and hand controller data. We hosted load test events on high powered, 96-core servers with well over 450 actual human operated avatars interacting together in the same virtual space. Not cheating with multiple server shards, but in the same discrete space, together, while logging and monitoring the massive streams of data to further optimize and improve the platform.

Spring 2019 was a tough season for High Fidelity, when business circumstance pivoted the company away from the metaverse and production shifted towards a seemingly more commercially viable remote coworking product. The company's virtual world servers were abruptly taken offline. The metaverse project largely dropped off the radar. There's a lot of theories about why the company decided to sunset its metaverse project, and I'll not go into them here. What's important is that the company made core parts of the architecture open-source so it could survive exactly this kind of situation.

The Xerox Alto, first created in 1973, introduced the point and click desktop interface used everywhere today. It never went to market. Today, this interaction model is at the heart of every Macintosh and Windows computer. Similarly, we feel that the spatial computing architecture engineered at High Fidelity, and its progeny, will become the backbone of spatial computing for decades to come.

On surviving VR Winter

VR Winter is probably coming, but like the title says, we've been literally working from a volcano in the Canary Islands. It's keeping us warm and fired up. To that end, we're weaving together our own spatialized metaverse using some of the core architecture innovated at High Fidelity, Inc.

It is the small mammals that survived the ice age. We're not a big company by any means, we're just a plucky little startup who wants a metaverse. We're haven't got money to make sexy videos, our shares are currently worth way less than penny stock, we're not going to have a flashy "initial land offering" on a blockchain. In fact, we're going to stay away from using the blockchain for now. What we do have is more than enough server resources, donated to us by Amazon, Google and Digital Ocean via the WXR Accelerator and First Republic Bank. What we do have is a groundbreaking open-source metaverse engine, seven years in the making. Most importantly, what we have is an understanding of what needs to be done to get people to actually use it, and perhaps even love it. And as far-fetched as it may sound, we think we've got just enough technical skill and moxie to do it.

When VR Spring rolls around, the tulip bulbs we're planting should be positively beautiful, and one sunny day, we'd like to have you join us in the garden for tea and fancy little biscuits.

In our next post, we'll talk a bit about white-space -vs-authoritative product design.

Thanks for reading our blog!

Caitlyn & Maki

About Tivoli Cloud VR

Tivoli Cloud VR, Inc, is a type-C Delaware corporation founded on October 5, 2019 by Maki Deprez and Caitlyn Meeks, headquartered in San Francisco, CA and Adeje, Tenerife. The company takes its name from the lovely Italian town of Tivoli, Lazio, just outside of Rome. Famous for its beautiful fountains and gardens, the town has inspired numerous amusement parks and pleasure gardens. Tivoli Cloud VR is not affiliated in any way with Tivoli Systems Inc, IBM Tivoli, or Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen.